Remaining, Waiting for Expansion (Again) The Islamic State’s Operations in Iraq and Syria

Source:

Over the past few years, focus on the Islamic State has rightfully expanded beyond its original territorial holdings in Iraq and Syria. Many of the activities that animated the organization’s core have been carbon copied to varying degrees by its global provincial network, with IS’s General Directorate of Provinces encouraging territorial control and governance, foreign fighter mobilization, and external operations planning.1 Today, the Islamic State controls territory and has governance projects at different levels in four African countries—Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, and Mozambique—as well as small foreign fighter mobilizations in these countries and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.2 More immediate from a Western security perspective is the growth in external operations from the Islamic State’s Khurasan Province (ISKP).3 These issues will continue to remain at the forefront of security discussions related to the future of the Islamic State. However, the original Islamic State base in Iraq and Syria remains relevant due to its historical importance and the uncertain status quo in the region since Islamic State lost full territorial control in Syria in 2019, especially when considering the future of U.S. military presence in the region.

On September 6, 2024, the United States and Iraq reached an agreement on plans to withdraw the U.S.-led “Global Coalition Against Daesh” forces from Iraq and Syria.4 Under this plan, there would be an initial withdrawal of troops from Iraq proper by September 2025, with the remainder leaving Iraqi Kurdistan by the end of 2026. This would also mean, in effect, a withdrawal from Syria.5 This will have monumental ramifications for the fight against the Islamic State in its original area of operations.

To better assess the current and future status of the Islamic State in these two countries, this paper leverages various data streams to provide a holistic picture of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria today. Each country features different dynamics, of course. Yet, by exploring Islamic State attack dynamics from various sources (including addressing the issue of underreporting claims in Syria) and publicly disclosed arrest details (local arrests as well as international arrests related to external operations), and continued shadow governance in eastern Syria, this report highlights how the Islamic State has attempted to recover over the past five years and seeks to take advantage of future change in regional dynamics.

Today, the Islamic State in Iraq is the weakest it has ever been, but the Islamic State in Syria has shown signs of building itself back up. Therefore, by understanding the current state of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, we can gain a greater understanding of the organization’s historic power base, its global expansion, and why it is not a relic of the past.

The Islamic State in Iraq

Overall, the current state of the Islamic State in Iraq is one of the few positive stories related to the jihadi movement in general and the Islamic State in particular. Counterterrorism efforts have had marked success degrading the group’s capabilities and reach within Iraq today. For the most part, the Islamic State no longer affects daily life within Iraq. Most of its attacks now occur in rural or very sparsely populated areas and when it does attack, the Islamic State is primarily focused on different sectors in Iraq’s security services rather than civilians. While the Islamic State may appear to be predominantly a law enforcement issue in Iraq, Islamic State-related arrests by the Iraqi state and Kurdistan Regional Government demonstrate that many remnants of the group from its territorial days remain at-large and current members of the group continue to plot and operate—regardless of the organization’s campaign-level fighting capabilities. Therefore, while it is important not to inflate the threat from the group, caution is appropriate in order to not overemphasize the group’s defeat in light of the Islamic State’s history of resurgences, which is a particular danger now that the United States looks set to withdraw from Iraq. The Islamic State is a complicated threat that needs continuous pressure to keep under control, since its fighters continue to have the will to fight, if at a lower capacity than previously possible.

Analyzing attacks

The Islamic State and its predecessor groups have constituted one of the deadliest insurgencies in the world since operations began in Iraq in 2002. When the organization expanded first into Syria and later into various other parts of the world, Iraq nonetheless remained the most active and violent of the Islamic State’s provinces for many years until 2022, when the Islamic State’s operations in Nigeria overtook those in Iraq.6 Ever since then, the Islamic State in Iraq has continued to decrease in violent activity relative to the other Islamic State provinces. For example, the Islamic State of Iraq has been the fifth most frequent province to claim responsibility for violence in the first half of 2024, behind Nigeria, Syria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mozambique.7 To better understand this precipitous drop, the past five years of attack data illustrate this point:

- 2019: 1,252 claimed attacks in Iraq

- 2020: 1,459 claimed attacks

- 2021: 1,127 claimed attacks

- 2022: 484 claimed attacks

- 2023: 151 claimed attacks

- 2024: 66 claimed attacks (as of November 14); on pace for 75 by the end of the year

The current pace of claimed attacks equates to a 49% drop from last year’s total and a 94% drop since 2019. However, one might question the veracity of the Islamic State’s self-reported attacks. There is ample evidence from next door in Syria that the group is underreporting its attack claims—a point which will be discussed in greater detail in the next section. When cross-checking it with data from Joel Wing, who has been tracking the Islamic State in Iraq closely since 2008 and relies on local reporting of Islamic State attacks (as opposed to self-reported attacks), the drop in claims within the Iraqi context still seems apparent. Wing’s data for the past five years shows:8

- 2019: 1,147 reported attacks

- 2020: 1,026 reported attacks

- 2021: 839 reported attacks

- 2022: 483 reported attacks

- 2023: 134 reported attacks

- 2024: 58 reported attacks (as of November 14); on pace for 67 by the end of the year

Of course, there are discrepancies in the two datasets, which could suggest either that local sources are underreporting Islamic State attacks within Iraq or that the Islamic State has been claiming more attacks than it has actually conducted in Iraq over the past five-and-a-half years. Nevertheless, what cannot be disputed is that the overall trend line is quite similar across the two datasets. Thus, when putting these two datasets together, it is highly unlikely that the Islamic State is underreporting claims of attacks in Iraq to the extent that it has in Syria. Therefore, on the whole, the Iraqi government, Iraqi Kurdistan, the United States, and the Global Coalition have clearly succeeded in degrading the Islamic State in Iraq from a relatively robust insurgency in the late 2010s to a manageable terrorism challenge. Put another way, at its height in 2014, the Islamic State averaged 28 attacks per day in Iraq and by 2023 it was averaging only 0.3 attacks per day.9

Arrest campaign

As a consequence of the lower rate of attacks, much focus in recent years has been on the lawfare aspect of the fight against the Islamic State through the arrest of operatives, fighters, financiers, and others. Since the beginning of 2023, the government of Iraq and the Kurdistan Regional Government have conducted 125 arrest cases against Islamic State cells as of November 18, 2024.10 While the map below shows that there have been arrests in different parts of Iraq, most of them have occurred in the provinces of Baghdad (31), Ninawa (14), Sulaymaniyah (13), and Kirkuk (10). A number of arrests (five) relate to past attacks such as the infamous Camp Speicher massacre of June 2014, when the Islamic State summarily executed at least 1,500 Shia cadets of the Iraqi military near Tikrit.11 Similarly, authorities have arrested Islamic State members in connection with their role in the subjugation and genocide of the Yezidi population in Sinjar.12 This included Asma Muhammed, one of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s wives, who was sentenced to death in July 2024 for crimes that include “detaining Yazidi women in her home.”13 These arrests suggest that although many Islamic State members and fighters were killed and arrested in the military campaigns that ejected them from their territorial strongholds in Iraq between 2014 and 2017, there likely remains an unknown number of residual Islamic State members still at large from that era.

Figure 1: Location of Islamic State arrests in Iraq between January 1, 2023, and November 18, 2024 (source: Aaron Y. Zelin)

This hypothesis is supported by deeper analysis of some of the arrest cases, which include many members who had been a part of the Islamic State bureaucracy during its heyday. For example, eight individuals were arrested in late April 2023 who had been a part of the Islamic State’s Diwan al-Jund (Soldiery Administration) and had been supplying food to different cells in the Kirkuk region.14 There is also the case of Akkab Hamad Nijris Dali (a.k.a. Abu Jamal) who was arrested in Sulaymaniyah in connection to his previous role as a sharia judge within the Islamic State’s Wilayat al-Dijlah (Tigris Province).15 Dali had fled Iraq to Syria in 2017 after the Islamic State lost territory in the former but returned to Iraq in 2023, illustrating how remnants of the group still traverse the two countries. Similarly, an Islamic State financial administrator based outside Iraq was attempting to resume his activities inside the country when he was arrested upon crossing the border with forged documents in February 2024.16 Likewise, former female members of the Islamic State have recently been arrested, including a woman who was previously a part of the infamous all-female al-Khansa Brigade in Iraq’s Ninawa governorate. She had been responsible for the Women’s Affairs Prison Administration during the Islamic State’s period of territorial control and had more recently been distributing funds to Islamic State-affiliated women in the region.17

Even more worrisome are the members of the Islamic State who have not yet been apprehended. The threat from those still at large is illustrated by recent cases, such as the former Islamic State emir (regional leader) Soqrat Khalil Isma‘il, who was arrested in Erbil in May 2024 after entering from Türkiye with a false passport.18 Isma‘il originally joined the Islamic State in 2013 and had initially been responsible for building explosives before participating in the 2014 takeover of Mosul and later rising to several leadership positions, including as a close confidant of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and emir. He remained in Mosul until the city was recaptured by Iraqi forces in 2017, then crossed over to Syria. Yet in 2018, he returned to Mosul under a false passport to collect five million U.S. dollars the Islamic State had hidden in the city, transferred the funds to Islamic State leaders in Baghdad, and then fled to Türkiye for five years before returning again to Iraq’s Kurdistan Region. It would not be surprising if there are other important Islamic State figures who, like Isma‘il, are operating undetected in Syria or Türkiye but are able to take advantage of the Islamic State’s cross-border networks and transit across the region.

Beside those who had previously been members of the Islamic State during its period of territorial control, others have been arrested for more current activities. In August 2023, a man was arrested in a Baghdad hotel for “carrying out intelligence-gathering missions” for the Islamic State and providing the organization information about members of the security forces in Ninawa governorate.19 Another individual in Iraq was arrested for issuing Islamic State fatwas that encouraged enlistment in the group and migration to Islamic State-controlled areas in Africa.20 It is plausible that this individual may have had a role in the June 2022 publication of the Islamic State’s al-Naba editorial titled “Africa Is a Land of Hijrah and Jihad.”21

In the realm of terror financing, Iraqi police seized a Kirkuk-based money exchange house in May 2024 and arrested two of its bankers for transferring money to the Islamic State from neighboring countries.22 Individuals also continue to extort Iraqi civilians to raise funds for the Islamic State, as seen in the case of Islamic State member “Abu Hajar” who was arrested in Tarmiyah in August 2024 for threatening district residents while using the name “Wilayat Shamal Baghdad.”23 While some Islamic State suspects have been arrested for violent extortion, others were arrested in August 2024 distributing funds to Islamic State families in Diyala.24 This goes to show that while it is true that the Islamic State does not possess its former military capabilities, the group continues to operate on different fronts.

Beyond Iraqi efforts to combat the Islamic State in the country, the government has had to focus on handling and fighting against the Islamic State within the prison system as those incarcerated attempt to restructure and plan for the future of the Islamic State. This should not be a surprise considering the Islamic State’s roots in the Iraqi prison system. The infamous Camp Bucca was where Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was famously detained during the U.S. occupation and became known as a university for jihadist networking, information sharing, and planning.25 More recently, the “Breaking the Walls” prison breakout campaign in 2013–2014 helped resupply the Islamic State’s fighting force as it took more territory in Iraq in the first half of 2014.26 The importance of controlling Islamic State members and sympathizers in the prison system helps explain the Iraqi perspective when, in mid-April 2023, eight Iraqis were sentenced to death for “restructuring” the Islamic State within the Rusafa prison and planning a prison break to rejoin the organization.27 Likewise, four former prison guards were sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment by the Rusafa Criminal Court for providing Islamic State prisoners with cell phones in return for bribes.28 These convictions underscore how, even after the many iterations of the Islamic State Iraq has seen since 2003, corruption within the prison system continues to allow the Islamic State to build and maintain influence.

Therefore, when looking beyond the claimed and locally reported attack data or the arrest information related to the Islamic State’s activities in Iraq, there are worrying signs that the organization is still a significant threat. This is particularly the case when considering those from the group’s period of territorial control who might still be operating undetected and waiting for an opportunity to take advantage of the changing political environment within Iraq, especially if and when the United States withdraws.

External operations

Beyond this local angle, there have also been indications that the Islamic State in Iraq has recently become involved in external operations planning in a manner not seen since the height of its territorial control in both Iraq and Syria. In particular, there have been three plots foiled thus far.

The first of these plots was stopped by Kuwaiti authorities in January 2024, when two citizens returned from training in Iraq and were tasked with conducting an attack at home by a Kuwaiti IS operative called “al-Shatri.” Once in Kuwait, they recruited two friends and remained in touch with al-Shatri. Iraqi authorities learned of the connection after interrogating a captured Islamic State operative and informed Kuwaiti security services, who broke up the plot.29

The other two plots were undertaken in Germany and were disclosed in May and June, respectively. In the first, an Iraqi national identified as “Najem A. M.” was arrested in the Bavarian town of Kaufbeuren for belonging to the Islamic State. He had joined the organization in Iraq no later than December 2016 and had worked in its “police force” when it controlled territory there. After entering Germany in early 2023, he maintained his connections with the Islamic State in Iraq and was preparing to carry out operations on its behalf. In autumn 2023, he received $2,500 from the group, likely related to his attack plot, which was eventually thwarted by German security services.30 In the second German case, an Iraqi identified as “Mahmoud A.” was arrested in the town of Esslingen southeast of Stuttgart for plotting to carry out attacks in Germany. He had joined the Islamic State in May 2016 in Iraq and had fought there on its behalf. He arrived in Germany in October 2022 and was awaiting orders to conduct attacks before he was arrested.31

These three plots, one in Kuwait and two in Germany, show that while there has been an understandable focus from counterterrorism practitioners and analysts on the external operations related to the Islamic State’s Khurasan Province in Afghanistan, the Islamic State has broader external operations ambitions that are being planned across its provincial network via the General Directorate of Provinces. This holds true for the Islamic State’s organization in Syria as well.

The Islamic State in Syria

Until 2024, the patterns of attacks and arrests in Syria looked very similar to those in Iraq. However, the Syrian context is different than Iraq’s, as the Islamic State appears to be underreporting attacks in Syria. Therefore, when comparing the Islamic State’s current status and likely future trajectory in the two countries that formed part of the Islamic State’s self-declared caliphate, the picture is most concerning in Syria. Part of this is due to the fact that Syria continues to retain elements of a civil war, albeit a somewhat frozen one. As a result, there is no one single governing authority that controls the entire country. Rather there continues to be contestation between Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian Arab Republic, which is backed by Russia, Iran, and a host of Shia jihadi foreign fighters; the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), which is primarily backed by the United States; the Syrian Interim Government, which is backed by Türkiye ; and the Syrian Salvation Government, which is managed by the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

This patchwork governance enables the Islamic State to take advantage of security seams between these polities, especially as actors in different locales try to undermine the security of their adversaries. For instance, the Assad regime and Iran have backed Arab tribal forces in Deir al-Zour province to instigate uprisings against AANES’s military, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), in an effort to undermine the SDF and U.S. positions in eastern Syria.32 This has undermined intelligence efforts by the United States and the Global Coalition and SDF in their fight against local Islamic State networks in eastern Syria. Additionally, elements of the SDF trace their origins to the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD), the Syrian branch of the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK), which is a U.S.-designated terrorist group and has had a decades-long history of conducting terrorist attacks within Türkiye. As a result, the Turkish government has conducted airstrikes against the SDF in northeast Syria and backed its own Syrian proxies to fight the SDF on the ground—principally through the Syrian National Army, which is the military formation for the Syrian Interim Government and is based in north-central Syria. As a result, the SDF has not been able to utilize all of its security resources to fight against the Islamic State.

Two developments in October 2023 likewise advantaged the Islamic State. The first was HTS’s drone attack against a graduation ceremony for one of the Assad regime’s military colleges in Homs.33 This led the Assad regime and its Russian allies to draw forces away from the western side of Deir al-Zour province to focus on attacking HTS’s base in Idlib in northwest Syria.34 This gave more breathing room for Islamic State activity across the frontlines between the Assad regime and SDF-controlled territories. Moreover, following Hamas’ October 7 attack and the subsequent response to Israel’s war in Gaza by Iranian-backed Shia militias in Iraq and Syria, Iranian-backed forces began targeting U.S. assets and bases in different parts of eastern Syria.35 As a force protection response, these attacks resulted in U.S forces and the Coalition limiting their actions against the Islamic State—either independently or alongside the SDF—providing yet another avenue for the Islamic State to operate.

As a result, Syria is currently a far more complicated space than Iraq and provides areas where the Islamic State can take advantage of instability and competitions among the various actors in the Syrian conflict.

Analyzing attacks

Since the Islamic State lost its last semblance of territorial control over Syria in March 2019, the number of claimed attacks by the Islamic State in Syria has significantly decreased every year. That changed in 2024, when, in contrast to the situation in Iraq, the Islamic State’s claimed attacks increased due to the factors outlined above:

- 2019: 1,055 claimed attacks

- 2020: 608 claimed attacks

- 2021: 368 claimed attacks

- 2022: 297 claimed attacks

- 2023: 121 claimed attacks

- 2024: 259 claimed attacks (as of November 14th); on pace for 296

If the numbers hold true through the end of 2024, this will equate to a nearly 250% increase since 2023, reaching parity with the rates in 2022. However, these claimed attacks do not capture the whole picture. Unlike in Iraq, where there is no evidence that the Islamic State is manipulating attack claims, there has been significant evidence suggesting that the Islamic State has purposefully underreported its claims in Syria to make it appear weaker than it actually is. Various researchers such as Aymenn al-Tamimi, Haid Haid, Gregory Waters, Charlie Winter, Devorah Margolin, and this author have recognized that the Islamic State has been underreporting its attacks in different parts of Syria, including the “badiyah” Homs desert region, in Hawran in southern Syria, and in the SDF-controlled areas of eastern Syria.36

This has also been corroborated through a series of leaked internal Islamic State documents originating from the fall of 2020.37 According to these internal documents, the rationale for underreporting the number of attacks appears to be threefold: first, worries that greater enemy action (meaning both the Assad regime and anti-regime rebels) might result against the Islamic State if it were to publicize all of the attacks it has conducted; second, a lack of communication and media equipment to record and share audio-visual coverage of the attacks to the Central Media Diwan; and third, a rift between media and military officials within the Islamic State, with the latter having operational security concerns and believing it is not necessary or advisable to claim every attack. While these documents are four years old, other data sources illustrate that this pattern began in 2020 and continues to this day.

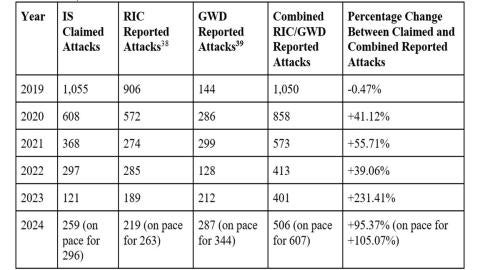

The SDF-aligned Rojava Information Center (RIC) publishes data on Islamic State sleeper cell attacks in SDF-controlled areas since the fall of the Islamic State’s territorial control. Similar to the Islamic State’s own attack claims, this RIC data should be caveated. When looking at the data side by side, it is important to acknowledge that the Islamic State’s claimed numbers cover all of Syria, while RIC’s are only for the AANES in the northeast of the country. One way of adding depth to our broader understanding of this issue is to additionally utilize Gregory Water’s dataset (GWD) on Islamic State activity in Assad regime-controlled areas, where the Islamic State is operating in what he describes as “Central Syria.” This region encompasses data from Islamic State attacks against “Syrian regime and allied fighters” in Deir al-Zour, al-Raqqah, Homs, Hamah, and Aleppo provinces, territory the regime controls and does not overlap with areas where the SDF or SNA are in control. Both the RIC and GWD have attack data through October 31, 2024.

Based on the below table, the RIC data suggests that Islamic State attack patterns in northeast Syria have been relatively stable since 2021 and have not actually gone down significantly in the past three years as claims from the Islamic State would suggest. As for the GWD-reported attacks, the information fluctuates but indicates that, after suppressing the group to some degree in 2022, the pivot by the Assad regime and Russia to combatting HTS in northwest Syria in the past year has provided more space for the Islamic State to increase attacks in Assad regime areas, with such attacks on pace to increase for the first time since 2019.

This is noteworthy when considering how the Islamic State might take advantage of a changed security environment once the United States withdraws from Syria at the end of 2026. There is strong evidence that the Assad regime and its allies will not be able to fight the Islamic State to the same extent as the United States, Global Coalition, and SDF, especially considering that the regime continues to view other actors such as the SNA, HTS, and remnant insurgent groups in southern Syria as greater threats to its rule than the Islamic State. The data below provides a stark warning about the potential for yet another reemergence of the Islamic State in Syria.

Table 1. Full spectrum data on Islamic State attacks in Syria since 2019, accurate as of November 18, 2024

The Islamic State’s policy of underreporting attacks has indeed been successful since it has in many ways lulled the United States and the Global Coalition into a false sense of accomplishment. The reality suggests that, while the Islamic State might be not as strong as it was around the time it lost its last territory in 2019, the organization is nonetheless two-to-three times as strong as its claims alone would suggest.

Shadow governance

Beyond the matter of parsing Islamic State attack data, the picture of the group becomes even more complicated when one begins to look at its shadow governance activity. Even if it is intermittent and less sophisticated than it was between 2013 and 2019, this has continued in eastern Syria since March 2019. This type of shadow governance assumes three characteristics: taxation, policing morals, and retaking territory (albeit briefly), with the former two showcasing that the Islamic State is still utilizing old administrative documents to pursue the shadow governance strategy.40

Since losing its territory in 2019, the Islamic State has continued to try and tax individuals at 2.5% the value of their earnings, savings, and goods in different parts of eastern Syria.41 According to local sources, the Islamic State is able to do this through a network of informants that “monitor sales locations, document quantities sold, and identify recipients.”42 Furthermore, the Islamic State threatens and extorts individuals via WhatsApp to secure such payments.43 These messages reportedly come from unknown numbers and one-day-used SIMs with alleged receipts bearing the Islamic State official seal,44 highlighting that the group is still attempting to act as a state with its old bureaucratic and administrative trappings. If someone does not pay, the Islamic State will threaten them with WhatsApp messages that state that “either you pay or you will be pursued by the organization’s cells.”45 If payments are still not forthcoming, the Islamic State will personally attack an individual or blow up their store, house, or car.46 So far, this sort of extortion and intimidation has been reported across eastern Syria,47 though it is likely these types of activities have also occurred elsewhere. There is further evidence that suggests the SDF has not sufficiently helped locals avoid these payments or track down the extortionists. For instance, one resident from the town of Dahla in Deir al-Zour stated that the SDF “advised him not to pay and assured him that these threats were nothing more than ‘mere threats.’”48

Another key component of the Islamic State’s governance infrastructure has been its hisbah(morality police), which has regulated the daily life of both men and women.49 In late May 2023, for example, Islamic State members posted official administrative documents on walls in mosques and public places in the town of al-Shuhayl in Deir al-Zour that ordered women to commit to the group’s version of modesty, including wearing the niqab under threat of punishment.50 Similar documents were found in the town of al-Tayana in August 2023.51 Although there has been less open source evidence of these types of activities in 2024, such activity is no doubt still occurring, especially in light of the continued taxation campaign.

The Islamic State also sometimes briefly or intermittently controls territory in northeast Syria. This tends to be a result of SDF constraints and security concerns, which mean SDF forces withdraw from some rural villages at dark each day.52 This gap has allowed the Islamic State to occupy parts of the villages overnight. In doing so, it not only undermines SDF operations in the area but also shows local populations that the organization remains undefeated and capable of exerting power, though not permanent control.

In March 2023, locals began describing the towns of al-Shuhayl, al-Busayrah, and Diban in Deir al Zour as the “Bermuda Triangle” due to the Islamic State’s sway over the areas.53 Moreover, in another leaked Islamic State document, the group claimed that 70% of its fighters were based in those areas.54 Residents have recently become too fearful to let the SDF know about the Islamic State’s positions in the region for fear of retaliation (which is facilitated by the Islamic State’s intimate knowledge of the local population from its past administration of the territory). For instance, one individual stopped by the Islamic State at a checkpoint in Diban was later found beheaded in a nearby town.55 Moreover, in July 2023, members of the Islamic State openly participated in a large caravan demonstration through the town of al Izbah against the recent burning of a Qur’an by an Iraqi Christian in Sweden.56

These data points paint a picture of the Islamic State still holding sway in many parts of eastern Syria. Considered alongside its increased attack tempo and underestimations of its strength, the Islamic State benefits from the current environment and would likely be able to take quick advantage of any U.S. withdrawal from Syria.

Arrest campaign

Although the Islamic State insurgency is growing and continues to embark on shadow governance activity, adversarial actors including the SDF, SNA, and HTS continue to independently arrest Islamic State operatives, fighters, financiers, and associates in Syria. Since the beginning of 2023, these forces have conducted 124 arrest cases against Islamic State cells as of November 18, 2024.57 While the below map shows that there have been arrests in different parts of Syria, most of them have occurred in al-Raqqah (29), around al Hol camp (19), and Deir al Zour (16). This is unsurprising considering al-Raqqah was the capital of the Islamic State’s Syrian territories during the group’s period of territorial control, Deir al-Zour has been the key location for the Islamic State’s continued insurgency since 2019, and the al Hol camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees is a locale of concern for many in the SDF and Global Coalition due to the strongly ideological Islamic State women who are detained there and continue to propagate the group’s creed to their children.

Map 2. Locations of Islamic State arrests in Syria between January 1, 2023 and November 18, 2024 (source: Aaron Y. Zelin)

Similar to arrest patterns in Iraq, many of those who have recently been arrested had previously held positions within the Islamic State during the period of territorial control. For example, the former director of the group’s Bayt al-Mal (Treasury) in Deir al-Zour was arrested in al-Raqqah in January 2023.58 That month, the SDF also arrested the former wali (governor) of the Islamic State’s Wilayat al-Raqqah, who had also led its Khalid Bin al-Walid Battalion.59

The most noteworthy operative arrested by the SDF was Yahya Ahmad al-Hajji (Abu Bara’ al-Hasa), who was arrested in the town of al-Busayrah in Deir al-Zour.60 Al-Hajji’s case is emblematic of those who had been in the organization during the period of territorial control and continued to operate for many years after the collapse of the territorial self-declared caliphate. Al-Hajji had originally been an assistant to Islamic State finance official Mamun al-Shami and subsequently became a financial officer for the Islamic State’s Syria province. He also worked in the group’s Military Command Council and was involved until his arrest in funding and organizing terrorist cells and recruiting other financiers. It is plausible that al-Hajji would have been involved in the “taxation” extortion racket that the Islamic State has continued to run in Deir al-Zour province as outlined previously.

Another similarity to Islamic State activity in Iraq are those individuals who left the theater of war, in this case Syria, and later returned to assist in continued operations. For example, Ahmad Fuwaz al-Rahman (Abu Uthman al-Barakah) moved to Lebanon in 2019 from Syria’s al-Hasakah province and reentered Syria in 2021. From there, he met with a cell in Dera’a in southern Syria and remained there until mid-2022 when he was instructed to join Katibat al-Zubair bin al-Awam, an undercover division based in his hometown of Hasakah, where he engaged in extortion rackets. (Al-Rahman was finally caught by the SDF in late April 2024.)61

Prison activity

In January 2022, Islamic State fighters attacked Sina’ prison in Hasaka, which housed thousands of male Islamic State prisoners, in a failed attempt to break them free. One of the attackers in the Sina’ attack was a deputy military commander of the Islamic State’s Wilayat al-Sham who was arrested for helping plan the Ghwayran prison break in November 2023.62 More recently, in mid-August 2024, the SDF arrested a cell of four Islamic State operatives who had been casing the al-Sina’ prison for a potential future prison break.63

A unique aspect of Islamic State operations in Syria is its involvement in smuggling activities in and out of al-Hol camp, which houses families of former Islamic State fighters detained in Syria. For instance, in early May 2023, two individuals were arrested by the SDF and Global Coalition for supplying weapons to cells in al-Hol and smuggling residents out of the camp.64 Only two weeks later, the SDF and Global Coalition arrested another cell in al-Karameh in Deir al-Zour for smuggling Islamic State detainees and families out of al-Hol to the towns of Ras al-Ain and Tal Abyad in north-central Syria.65 Similarly, in August 2023, an unidentified leader of an Islamic State cell based in the village of al-Izba was arrested by the SDF for providing fake identification cards, travel documents, and weapons to families seeking to flee al-Hol camp. This individual had also been facilitating the transport of explosives, weapons, and ammunition to Islamic State cells attacking SDF forces,66 illustrating that those working in facilitation and logistics for the Islamic State have dual hats serving the group’s insurgency as well as supporting camp residents. These smuggling activities have continued in 2024.67

In addition to al-Hol camp, there are camps housing the families of Islamic State fighters in the areas of north-central Syria held by the Turkish-backed SNA, specifically around Ras al-Ain and Tal Abyad. This is why many of those attempting to be smuggled out of al-Hol try to reach those cities: Syrians typically travel from those cities towards their original homes, while foreign fighters proceed to the border to try to reach Türkiye and start a new life. The camps in SNA territory have also seen smuggling activity, like the case of Islamic State operative Muhammad Mahmud Hamada who was arrested for smuggling members of the group’s “Cubs of the Caliphate” training program from those camps.68

Similar to the situation in Iraq, it is clear that veterans of the Islamic State from the period of territorial control remain at large and are periodically getting arrested in Syria. More worrisome are the continued efforts by Islamic State operatives to support different aspects of the growing insurgency in eastern Syria through, e.g., weapons procurement, intelligence operations, extortion, and smuggling. This data also makes clear that the Islamic State remains interested in prison breaks to free its fighters detained across northeast Syria and in smuggling women and their children out of al-Hol camp.

External operations

Since the beginning of 2024, the Islamic State in both Syria and Iraq have been involved in external operations planning in a way not seen since the height of the group’s territorial control. In particular, there have been three foiled plots and one successful one originating in Syria in 2024.

The first came to light in late February, when Israeli security services arrested four Palestinians for manufacturing approximately one hundred explosive devices. The head of the cell had made the explosives using online guides as well as instructions he received from Islamic State operatives in Syria. The cell also possessed assault rifles and submachine guns and was planning to attack Israeli troops in the West Bank.69

Subsequently, in May 2024, an eighteen-year-old Russian national from Chechnya was arrested for plotting to attack a stadium during the Olympics in Saint-Etienne, France. He had communicated online with a Chechen Islamic State operative based in Syria and had surveilled the stadium ahead of his arrest.70 Then, in August 2024, Russian authorities arrested six people, including three minors, in the city of Nazran and the village of Kantyshevo in Ingushetia for planning to attack an Orthodox church and to carry out attacks against security forces. The individuals had reportedly pledged allegiance to the Islamic State’s “caliph” and received instructions from handlers in Syria.71

Most notably, on August 23, 2024, a Syrian national killed three individuals and injured eight others in a stabbing attack in the town of Solingen in the German province North Rhine-Westphalia. Before the attack, the assailant had recorded a video in which he pledged allegiance to the Islamic State’s “caliph” and said that the attack was revenge for the “massacres of Muslims” in Bosnia, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine.72 The individual was originally from the town of al-Mari’iyah in the eastern countryside of Deir al-Zour, where he had previously been recruited to work in the Islamic State’s zakat office alongside his cousin. (Five of his relatives had also become members of the Islamic State.) The attack was similar to the two foiled attacks in Germany mentioned in the previous section, in which the Islamic State sent two separate operatives from Iraq to Germany to conduct stabbings. Therefore, it would not be surprising if we were to see similar plots in the future originating from either Iraq or Syria.

The Future of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria

The future trajectory of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria will be determined in large part by the future of the U.S. military presence in the region. Due to the counterterrorism successes against the group in Iraq, the Iraqi government wants to rearrange its security relationship with the United States from one based on the Global Coalition to one that is purely bilateral.73 The potential issue there is that the Global Coalition’s mandate provides legal cover for U.S. forces to operate in eastern Syria alongside the SDF, by extension helping to safeguard Iraq’s border from Islamic State cells. A bilateral agreement, however, could terminate the legal basis for U.S. forces to operate in Syria.74 While the Islamic State is not nearly as strong in Syria as it was a decade ago, it still sustains a robust insurgency and would no doubt take advantage of any withdrawal of U.S. forces.

One could imagine a cascading effect of adverse consequences: U.S. forces withdraw from northeast Syria, Türkiye takes advantage of the U.S. absence to increase its attacks against the SDF,75 the SDF withdraws from Deir al-Zour to safeguard the Kurdish heartland in Hasakah, and the Islamic State exploits the situation by attempting to break out its former fighters from the SDF prison system (the Assad regime and its allies, all the while, would likely continue to fail to meaningfully suppress Islamic State activity in its own territory).76 This likely conflagration could allow the Islamic State to once again carve out territorial control in eastern Syria and use the space to reseed its insurgency in Iraq.77

As part of its effort to mitigate infiltration by the Islamic State’s Syrian cells into Iraq, the Iraqi government has begun building a concrete wall along its long border with Syria.78 However, the wall presently covers only 100 of the 373 miles of the border, and, more importantly, it is likely that the Islamic State would simply build a tunnel system under the wall if it were ever completed. Iraqi security forces have indeed already discovered two Islamic State tunnels measuring 165 feet long and 6.5 feet high that acted as a command center in the village of Abu Mariya in the Tal al-Afar district.79 It is unlikely, then, that Iraq would be able to fully contain the fallout from any Islamic State resurgence in Syria.

These are worrying signs for the future. Delinking the two theaters, as the Iraqi government has attempted to do, is a recipe to potentially repeat history wherein the Islamic State in Syria regains strength and pours resources back into its operations in Iraq. The timing of this could not be any worse with the planned U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq and Syria over the next two years. The United States continues to conduct airstrikes against key Islamic State networks on both sides of the Iraq-Syria border,80 and it is unclear if such operations could be conducted under some “over-the-horizon” policy. As has been apparent following the withdrawal from Afghanistan, U.S. counterterrorism operations can be limited by adversarial or uncooperative actors, such as the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate in the case of Afghanistan (and the Assad regime in the potential case of Syria).

Relatedly, the recent coups in the jihadism-afflicted Sahel region of West Africa—which have resulted in Russian mercenaries replacing Western militaries in supporting the counterterrorism efforts of the new military regimes in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—point to another possibility if the Islamic State were to reemerge in Iraq or Syria: With Russia remaining next door in Syria and with the tightening relationship between Russia and Iran (and Iran’s proxies in Iraq continually wanting to squeeze any regional U.S. military presence), will Iraq ask Russia to take over as its key counterterrorism patron after U.S. forces withdraw? In such a scenario, the United States and its partners would be shut out of the three major hotspots in the world where jihadist activity is most acute (Iraq and Syria, Afghanistan, and the Sahel).

The stakes are therefore quite high. If the United States repeats the same mistake it did in 2010 when it withdrew the bulk of its forces from Iraq, there could be a renewed Islamic state threat within Syria and Iraq with global implications. But, potentially unlike in 2014, the United States might be unable to mitigate this issue militarily, instead being at the whim of adversarial actors who would leave Washington with far fewer options to deal with the problem.